CITEULIKE: 1431690 | REFERENCE: BibTex, Endnote, RefMan | PDF ![]()

Aart, J. v., Klaver, E., Bartneck, C., Feijs, L., & Peters, P. (2007). Neurofeedback Gaming for Wellbeing. Proceedings of the Brain-Computer Interfaces and Games Workshop at the International Conference on Advances in Computer Entertainment Technology, Salzburg, pp. 3-5.

Neurofeedback Gaming for Wellbeing

Department of Industrial Design

Eindhoven University of Technology

Den Dolech 2, 5600MB Eindhoven, NL

design@joran.eu, e.r.g.klaver@student.tue.nl, {c.bartneck, l.m.g.feijs; p.j.f.peters} @ tue.nl

Abstract - In this paper we discuss our vision on future neurofeedback therapy. We analyze problems of the current situation and debate for a change in focus towards a vision in which neurofeedback therapy will ultimately be as easy as taking an aspirin. Furthermore we argue for a gaming approach as training, for separation between neurofeedback therapy and gaming has become noticeably smaller after recent development in brain manipulated interfaces. We conclude by providing suggestions of how to achieve this vision.

Keywords: Neurofeedback therapy, neurofeedback training, gaming, EEG, mental and physical wellbeing, prevention as healthcare

Introduction

Neurofeedback [2], as therapy of the future, may realize the vision of fighting the cause rather than the symptoms. It treats health problems like attention deficit disorders, hyperactivity disorders and sleeping problems, formerly all suppressed with medication. Based on EEG measurements, the user’s mind is trained to bridge new connections and to either increase or decrease the use of specific brain functions. And best of all: it is achieved by simply undergoing a number of non-intrusive sessions, which we propose to improve by interconnecting with gaming appliances. However, if it is such a promising concept, why hasn’t this therapy been adopted by the general public and health companies yet?

Review

The results of research in the field of neurofeedback seem very promising, but various aspects like discrepancy in society focus, general acceptance and practical issues (time and money) form challenges that have yet to be overcome.

In present day society, people only consult a doctor when experiencing physical complaints. In other words: the focus is too much on the physical aspect of health and on curing the symptoms. In contrast, the main focus of neurofeedback is on mental issues, e.g. concentration or sleeping disorders and on fighting the cause of these disorders, rather than the symptoms. The gap between the health focus of society and neurofeedback therapy is noticeable, which may be one of the reasons that neurofeedback is not applied to its full potential yet.

For neurofeedback to be integrated in society, there is a need for neurofeedback to be accepted. However, another problem might be that neurofeedback therapy is based on a ‘mind over matter’ perspective, implying that not only the physical and mental wellbeing are interconnected [3, 5] but also that the physical wellbeing can actually be a result of the mental one. Although this statement has been proven in various studies [3], people may experience problems with acceptance. Ungrounded conservative opinions have been formed, perhaps as a result of the natural fear of the unknown. Still, although neurofeedback therapy has shown to have a positive influence [6] on numerous disorders, absolute and undeniable proof of absence of possible side-effects has not been supplied yet. Whether this is a potential issue for the therapy not to be accepted, remains open for debate. However, it has been said that if some or another medication could be as broadly and effectively applicable as neurofeedback therapy, it would already be available at every pharmacy in the world. [11]

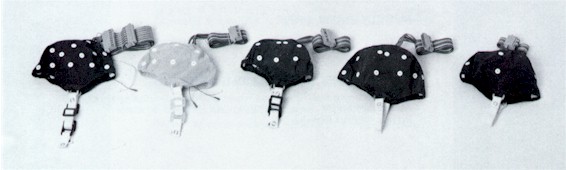

More practical problems with neurofeedback therapy (compared with for example medication) include its expensive and time consuming aspects. Currently, a regular therapy exists of approximately 40 sessions of 1 hour each, preferably one or two sessions a week. However, this hour includes only 30 minutes of actual contact time, since existing EEG products simply take a lot of time to prepare. A closer look at the method: In most cases, EEGproducts involve placing an elastic cap on the head, with 19 sensors held in place on the scalp. To optimize scalp contact, dead cells are removed and hair is parted out of the way to place sensors with gel on the scalp. The ElectroCap (see Figure 1) [1] is the far most used example of this category. Other cases include the use of a 2-channel EEG measurement, involving only 2 sensors and clips on each earlobe. In those cases, the sensors are placed on the scalp directly (without the elastic cap), for the cap mainly functions for defining the location of scalp electrodes.

Besides the extensive preparation, these sessions take place at a clinic, therefore waiting time and obviously travelling time should be counted as well. Besides the time aspect, neurofeedback therapy is very expensive and not refunded by health insurances. The identified issues, varying from practical to emotional, might all slow down the development of neurofeedback therapy and its acceptance by society.

Aim

We suggest a change in the focus of neurofeedback in two ways, both the aim as well as the practical realisation. Furthermore we emphasize the importance of intrinsic motivation (gaming) [9] in neurofeedback training. As applied for health-related training systems, current aims of neurofeedback therapy might include:

- training to improve overall fitness;

- training to alleviate attention and hyperactivity disorders, e.g. for ADHD patients;

- training for specific sports such as rowing, cycling etc.;

- training for relaxation and meditation to cope with mental strain;

- training muscular tonicity recovery for cardiovascular patients;

- training and eating schemes to maintain proper weight or loose overweight.

Aims described above, include therapies applied in the medical area, focusing on people with mental disorders. Using neurofeedback training they are able to improve their quality of life and bring their wellbeing level up to a regular standard. But what if we would apply this therapy before any disorder has occurred? Given the fact that both mental and physical health are interconnected [3], neurofeedback therapy could function as prevention rather than a cure. This insight brings closer the European dream, emphasising quality of life over accumulation of wealth [10].

Imagine the possibilities of using neurofeedback training as tool to improve the quality of our lives; consequences on a macro scale would be immense, ranging from a decrease in diseases to a reduction of health insurance fees. As a matter of fact, this shift of focus from cure to prevention is already taking place in healthcare; a Dutch health insurance company actually stimulates the use of low-cholesterol margarine by partly refunding it [8].

Using neurofeedback training as tool to improve life would be a big step in healthcare. It could be argued that healthcare uses neurofeedback to elevate wellbeing to certain standards, while professional athletes use neurofeedback to enhance their already exceptional performances; the so-called field of peak-performance. With neurofeedback therapy, athletes are able to teach themselves to consciously enter a state of ‘relaxed focus’, resulting in an optimal performance also known as the winning mood. Now imagine that everyone could consciously evoke this feeling; neurofeedback could be used to not only cure or prevent diseases but to elevate our entire standard of living.

However, before neurofeedback training is accepted, there’s a need to cope with multiple challenges neurofeedback is facing, for example the practical issues described before. Neurofeedback therapy currently involves a lot of time, money and other practical issues which can obstruct the acceptance of neurofeedback therapy. We suggest a world in which neurofeedback training is as easy as taking an aspirin.

To realise this vision, we suggest home-use should be enabled. For this to happen, first of all the involvement of a medical expert should be decreased (e.g. only for guidance in defining the goals and keeping an eye on the progress). Of course, it is still strongly recommended to undergo a medical investigation, to exclude certain causes of possible complaints and to check for counter-indications.

Our second suggestion is that a user should be able to conduct a therapy session independently. This implies the need to be able to easily locate the necessary contact-points and applying the sensors. It can be assumed that most of the households already have a computer which can calculate sensor input and provide feedback. This means that in principle, only an EEG measurement device and a software package needs to be applied, which would greatly reduce costs. As a final demand, the training software should be easy to operate and perhaps even more important: the software should be intrinsically motivating (playful).

Based on observations, the following assumptions are formulated, which could be advisable to keep in mind when designing for playful neurofeedback training sessions:

- A1: that it is helpful to give the user rewards based on performance;

- A2: that it is helpful to simulate elements from an assumed context of use;

- A3: that it is helpful to provide the user with quantitative performance data.

Similarities between gaming and neurofeedback training software are identified, for example: reward schemes with levels, credits, bonuses, etc. (A1), sound generation and rendering of high-resolution real-time environments (A2), statistics and graphs etc. (A3). Given the fact that intrinsic motivation is found in gaming [7] and that it provides positive influences on concentration and motivation, we suggest to focus on gaming when creating neurofeedback training software (e.g. ‘Brainball’ of Hjelm [4] is considered to be an interesting example). Imagine neurofeedback, applied as a treatment, being perceived as fun and enjoyable. In this case a shift from ‘treatment’ to ‘play’ could be both desirable and achievable. It should be kept in mind however, that gamers might not be satisfied with any rewards, contexts and data that are much more naïve and low-tech than their media experience; or in other words: neurofeedback training might have to keep pace with gaming.

Approach

In this section, issues that are possibly slowing down the development of neurofeedback will be addressed. Suggestions for realising the proposed aims of neurofeedback gaming will be discussed as well, starting with the acceptance.

It is likely that, before society can accept neurofeedback, there is a need for awareness about the system and its functioning. This would imply that before society can exploit the various opportunities of neurofeedback training, such as improving personal capabilities, people need to be made aware of the possibility called neurofeedback training. For this to be reached, we should realize that neurofeedback therapy (as applied at the moment) is the frontier of neurofeedback training. Early adopters like athletes and people with mental disorders presumably have a bigger drive to look further, which resulted into neurofeedback therapy. More might follow and neurofeedback could become more and more accepted when positive media attention keeps on going. Furthermore, part of this acceptance probably has to be achieved by means of scientific proof, especially regarding the governmental and health insurance area. Therefore we debate for large scale research proving the positive influence of neurofeedback therapy and the absence of negative side-effects.

However, increasing acceptance of neurofeedback therapy would only be the first step. We also propose to enable neurofeedback training controllable by the user in home context, which could be achieved by designing products according to specific user requirements. These requirements are based on the aim of shortening and simplifying the training methodology and would therefore include being able to:

- easily locate contact points

- easily apply sensors (including conducting gel) to one’s head

- have access to training software and the ability to control it

- receive feedback on electrode impedance and act accordingly

- easily clean the sensors and reuse the system

With these suggestions, time and money issues are addressed. Additionally, it is likely that neurofeedback would become available to a broader public. This might help to accomplish the aims regarding wellbeing (being: focus on prevention and mental health, increase capabilities by consciously training brain signals). We propose to increase accessibility of neurofeedback training in both a physical and social way. The physical accessibility (or easiness of home-use) combined with the social accessibility (or intrinsic motivation of gaming) logically increases enjoyment of the training. This could result in a consumer demand contributing to elevating the standard of living of the general public.

Additionally, specifically focusing on certain target groups may support development in crucial adoption stages. For example children with small attention disorders, who would normally never be treated or trained, can be reached by increased accessibility of neurofeedback.

Also, we consider playfulness to be another important factor of accessibility. When implementing gaming approaches as shown in assumptions A1 – A3, neurofeedback training could profit from keeping up with gaming. On the other hand, neurofeedback can be seen as an extension to the already existing tools for gaming; actually the only change in the gaming application would be the input. Instead of movement information sent by a mouse to the software, EEG signals are derived from the brain and used as input. In short: current gaming can be extended with EEG signals as input.

Conclusions

We identified several possible issues holding back the development and implementation of neurofeedback therapy. New aims of neurofeedback are suggested, including: 1) a focus shift (in healthcare) from cure to prevention, 2) increasing the focus on mental wellbeing in healthcare, 3) elevating the standard of living by enabling users to consciously train brain signals 4) implementing gaming approaches in neurofeedback to increase intrinsic motivation. In general, we propose to make neurofeedback training more accessible by designing single-user products for the home environment and thereby achieving our idea of using neurofeedback to its full potential. Furthermore we argue the use of gaming as motivational tool and to support society adopting neurofeedback training.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our colleagues at the Department of Industrial Design, Eindhoven University of Technology, who raised our interest and helped shaping our thoughts. Furthermore we would like to thank Pierre Cluitmans and Frans Tomeij for sharing their knowledge and insights on the matter.

References

- Electro-Cap International Inc. (2004). Electro-Cap International, Inc. Electro-Cap Retrieved April 3, 2007, from http://www.electro-cap.com

- Evans, J. R., & Abarbanel, A. (1999). Introduction to quantitative EEG and neurofeedback. San Diego: Academic Press. | view at Amazon.com

- Fox, K. R. (1999). The influence of physical activity on mental well-being. Public Health Nutrition, 2(3a), 411-418. | DOI: 10.1079/S1368980099000567

- Hjelm, S. I. (2003). Research + design: the making of Brainball. Interactions, 10(1), 26-34. | DOI: 10.1145/604575.604576

- Kendell, R. E. (2001). The distinction between mental and physical illness. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 178, 490-493. | DOI: 10.1192/bjp.178.6.490

- Lubar, J. F., Swartwood, M. O., Swartwood, J. N., & O'Donnell, P. H. (1995). Evaluation of the effectiveness of EEG neurofeedback training for ADHD in a clinical setting as measured by changes in T.O.V.A. scores, behavioral ratings, and WISC-R performance. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 20(1), 83-99. | DOI: 10.1007/BF01712768

- Malone, T. W. (1981). What Makes Things Fun to Learn?: A Study of Intrinsically Motivating Computer Games. PhD Thesis, Stanford University, Stanford.

- Munneke, W. (2006). Kennislink. Becel als medicijn Retrieved April 3, 2007, from http://www.kennislink.nl/web/show?id=145431

- Rauterberg, M. (2004). Positive effects of entertainment technology on human behaviour. In R. Jacquart (Ed.), Building the Information Society (pp. 51-58): IFIP, Kluwer Academic Press. | view at Amazon.com

- Rifkin, J. (2004). The European dream : how Europe's vision of the future is quietly eclipsing the American dream. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin. | view at Amazon.com

- Roskamp, H. (2007, feb/mar 2007). Wordt baas in eigen brein. Bright, 14, 57-61.

This is the authors' version | last updated February 5, 2008 | All Publications